Endless Prowl | Daniel Ford

That World: Latheism, Contextual Modularity, and World-Building as Philosophy and Art Practice

By Daniel Ford

Abstract

That World is a modular, interactive art system and research practice that challenges the boundaries between art and non-art, individuality and assemblage, singularity and multiplicity. Rooted in the emergent philosophy of Latheism, a cyclic, noninterventionist mode of creation inspired by practice based world-building, contemporary metaphysics of nothing, and the lived realities of neurodivergence, That World proposes and enacts an ontology in which meaning, agency, and context are perpetually negotiated. The project’s ethics are manifest in flexible, context-creating design, decentralizing authorship, and a refusal to predetermine experience, foregrounding parallels with neurodivergent cognition and challenging conventional hierarchies in both art and philosophy.

Introduction

Traditional approaches to accessibility and participation in art frequently operate as retrofitted accommodations: they add ramps, explanations, or alternative experiences to works already conceived within assumed thresholds and norms. In contrast, That World begins with the generative possibilities of context, modularity, and affordance, not as supplements, but as the ethical core of its design. Here, inclusivity is not the goal, but the condition of being. The artwork and system welcome and require uncertain forms of engagement, non-hierarchical expertise, and modes of co-creation.

Latheism: Correlationism, Contradiction, and the Undivided Whole

A central philosophical concern underlying That World is the status of relationality, contradiction, and perceptual co-production within artistic experience. This concern aligns with, and simultaneously extends beyond, the problem of correlationism as articulated by Quentin Meillassoux. Correlationism describes the post-Kantian claim that human thought can never access the world “in itself,” but only the relation between thought and world. Perception is not an encounter with an independent reality but a disclosure conditioned by the structures of the subject. As Meillassoux notes, what lies outside the correlation,what he calls the ancestral or the ‘great outdoors’,remains inaccessible except through its relation to human access.

In the context of That World, this philosophical lineage is important not because the work attempts to disclose a pre-human reality, but because its interactive behaviour makes the correlation visible. The installation exists only in and through the participant’s movement, presence, or intentional withdrawal; the audiovisual system does not reveal a stable world waiting to be accessed but continuously produces the conditions of its own relational becoming. Each canvas becomes an interface in which perception, movement, sensing technologies, and sound synthesis form a co-ordinated ecology of encounter. In Latheist terms, the world is not given, it is generated and regenerated through cyclic interaction, embodying correlationism not as limitation but as method.

However, Latheism does not remain within the correlationist framework. It deliberately mobilises dialetheism, the philosophical position (advanced by Graham Priest and others) that true contradictions can exist. The installation’s ontology of “art/non-art,” “presence/absence,” “object/system,” and “individual/multiplicity” constitutes a set of contradictions that do not resolve but coexist productively. The canvases featuring fabric and embroidery are artworks in their material construction, yet become non-art when functioning as instruments, sensors, and computational systems. They are present when responsive but equally defined by their periods of stillness, dropout, or silence. Meaning in the work arises from the tension between these incompatible states rather than from the elimination of contradiction.

This resonates with Suki Finn’s metaphysics of nothing, which argues that absences, omissions, and ‘nothings’ have genuine ontological force. In That World, technological limitations, such as the system’s momentary failure to track movement or the refusal of a module to activate, become meaningful elements that shape the participant’s experience. Silence, latency, or unresponsiveness are not treated as errors but as structural features that contribute to the installation’s relational ontology. The work thus positions “nothingness” not as void but as an active participant in the world-building process, aligning with Finn’s claim that emptiness and absence can possess real metaphysical weight.

This approach finds an unexpected parallel in contemporary quantum physics, particularly relational and process-oriented interpretations. In Carlo Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics, the properties of a system do not exist independently but only in relation to other systems. Likewise, in quantum field theory, so-called “particles” are excitations of underlying fields rather than discrete objects. There are no stable ‘things,’ only relations, events, and interactions. This aligns with Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy, where reality consists of occasions of experience rather than substances.

That World mirrors this quantum relationalism: its components, textile canvases, projection systems, MIDI mappings, sound engines, and participants,form an environment where no single element determines the world. Instead, the installation operates as an undivided whole, an entangled field of relations that continuously shapes and reshapes itself through interaction. The work is not a collection of objects but a distributed, emergent system in which agency and meaning arise through entangled processes.

This relational ontology also resonates with panpsychism, particularly contemporary forms that argue consciousness or proto-experience is a fundamental feature of physical reality (Strawson, Goff). That World does not propose that its components are conscious, but it adopts panpsychism’s distributed model of experience. The system behaves as though it perceives: it responds to movements, interprets silence, and produces emergent behaviours not reducible to any single component. Experience in the installation is co-produced,distributed across textile surfaces, sensor technology, sound synthesis, projection mapping, and participant engagement. The system is not alive, but it exhibits a form of responsiveness that destabilises the boundary between animate and inanimate, human and non-human, object and environment.

Latheism synthesises these philosophical strands by treating world-building as a cyclic, relational, and ethically charged process. It acknowledges the correlationist insight that worlds are accessible only through relations, yet embraces dialetheism’s acceptance of contradiction and Finn’s recognition of absence as metaphysically significant. It draws from quantum physics the notion that the fundamental units of reality are not things but interactions, and from panpsychism the idea that experience may be distributed rather than centralised. Within this Latheist ontology, That World emerges not as an artwork in the traditional sense, but as a world-system: an undivided, contradictory, relational whole that exists only through continuous negotiation between presence and absence, agency and limitation, human and non-human perception.

In this sense, That World embodies a model of artistic practice in which the artwork is neither an object nor a representation but a living epistemic ecology. It is a world that listens, responds, transforms, and occasionally refuses, an installation that enacts the ethical, metaphysical, and material propositions of Latheism through its own operational logic. By foregrounding relationality, contradiction, and the generative role of nothingness, the work challenges inherited assumptions about artistic authorship, aesthetic autonomy, and the boundary between art and non-art. Instead, it proposes a vision of practice in which worlds are built cyclically, collaboratively, and with an openness to the undivided whole from which all meaning emerges.

Modularity and Ethical Design

That World is comprised of three large textile canvases, each an individual entity but also a constituent of a larger installation, performance, or participatory system. Each segment features its own reactive light, projection, and sound interactivity: functioning as a solo work, as a trio ensemble, or in hybrid combinations.

The philosophy of modularity here becomes an ethics: users can approach, interact, and assemble the system according to their own context, choice, and sensory or cognitive needs. The elements’ independence and combinability are not mere technical features, but material expressions of Latheist cyclicity and the recognition that value emerges in relational, contingent, and non-finalized configurations, paralleling both Deleuzean assemblage and Finn’s philosophy of absence.

Morality and Agency

Ethically, That World foregrounds choice, openness, and unpredictability. No viewer or participant is forced into a predetermined experience; pathways through the work are defined through active encounter, in ways that foreground agency, boundary negotiation, and the refusal of normalization. Rather than “diluting” the work, the multiplicity of artistic and performative contexts gives rise to new forms of mastery, contradicting the stereotype that multiplicity implies a lack of depth (“jack of all trades, master of none”). Here, each module demonstrates both autonomy and capacity for deep entanglement, analogous to neurodivergent constellations of interest and the ADHD experience of non-linear expertise.

This parallels the idea that world-building, both philosophically and artistically, is a continuing act of possibility of configuration, and of creating contexts that enable new meanings to arise cyclically and collaboratively.

Context Creation and Neurodivergent Cognition

That World is not just a system; it is a context-generator. Like the neurodivergent or ADHD mind often characterized by concurrent pursuits, shifting focus and simultaneous mastery across domains, the work refuses the binary of artistic specialization and instead encourages multiple, intersecting forms of engagement, concentration, and play. The modular fabric of the work honors the so-called “weaknesses” of scattered attention or distributed effort as, instead, engines for innovation and parallel mastery.

Just as an ADHD or autistic mind may manifest polyphonic attention, That World enables simultaneous musical, visual, tactile, and interactive experiences, each complete alone, but richer in connection. Each visitor chooses their entry point, depth, and level of interaction, and the system reconfigures itself accordingly. This creates new contexts in real time, echoing the ethical principle that world-building is a shared, non-hierarchical process.

Philosophical, Moral, and Ethical Implications

On the philosophical level, That World moves toward a model of practice in which contradiction and incompleteness possess moral significance, embracing both absence and presence, success and visible failure as co-constituents of world-building. By integrating Finn’s metaphysics of nothing, and dialectics of presence/absence, the project affirms that the space of engagement and non-engagement, or accessibility and inaccessibility, remain legible and formative for experience, highlighting the parasitic nature these contrary elements encompass within the work.

Moral and ethical implications are thus inscribed in both design and reception: the system makes technological and social accessibility and inaccessibility visible, framing them as shared matters of concern, and inviting participants not only to explore “what is there” but also “what might be, or might not,” and highlighting how we name and discuss vague boundaries or entities. Participation is both individual (in modules) and collective (in installation), and the project is a space for difference, learning, and ongoing philosophical becoming rather than resolution.

Technical Construction and Navigating Accessibility Roadblocks

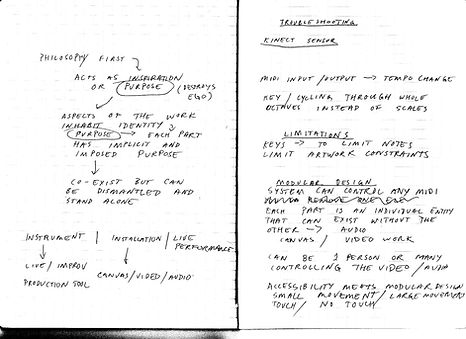

The development of That World has been as much a journey through technological complexity as it has been creative experimentation. Central to this journey was grappling with the inherent accessibility challenges embedded in interactive software systems and linking them together into one pipeline, particularly those linked to motion tracking and MIDI integration. These obstacles not only shaped the final form of the artwork but also became inseparable from the artistic practice itself, demanding ongoing technical reflexivity and iterative troubleshooting.

A persistent challenge was the system’s hand-tracking interface, which initially functioned akin to a theremin, an instrument known for its continuous pitch variation controlled through hand position. In early iterations, the MIDI interface mapped hand movements indiscriminately across entire octaves. This resulted in a raw and uncontrolled stream of notes, producing chaotic bursts of sound that overwhelmed any sense of musical or conceptual coherence.

Recognizing this cacophony as both a technical and artistic limitation marked a significant turning point. The focus shifted to calibrating the MIDI settings within Ableton Live to constrain the pitch range to a specific musical key. This tuning was not merely about fixing a bug; it emerged as a critical moment of carving out the system’s inherent limitations, defining the boundaries within which the installation could function thoughtfully and elegantly.

This limitation-driven approach ignited a deeper investigation into which sonic elements resonated best with the system’s interactive parameters. The choice of instruments, the responsiveness of synthesizers, and the behavior of arpeggiators became essential considerations. The Jupiter XM synthesizer, with its capacity for nuanced response, proved particularly compatible, offering rich, textured tones that harmonized with the evolving MIDI control patterns.

Selecting the appropriate arpeggiator was equally crucial. Its reaction to the cyclic MIDI input shaped not only the sonic rhythm but influenced participant engagement through temporal structuring of sound that was also consistent in its evolution while being activated. Together, these hardware and software decisions sculpted the emergent soundscape from potentially overwhelming noise into an engaging, listenable musical environment.

Thus, the artistic practice evolved hand-in-hand with technical problem-solving. Troubleshooting became a creative methodology, where understanding and working within technological constraints informed conceptual development. The iterative modulation of midi mappings, key restrictions, and instrument selection transformed That World from a reactive installation into a refined, context-sensitive, and embodied musical dialogue between performer, environment, and machine.

In this light, the roadblocks encountered became generative forces. They demanded attentiveness to system affordances, grounded aesthetic judgment, and an ethical commitment to crafting an experience accessible not through simplification, but through thoughtful orchestration of complexity within defined parameters. This integration of technology and art-making underscores that in practice-led research, technical mastery and conceptual inquiry coexist in an indispensable, dialogic relationship.

Research and Testing: Expanding Performance Boundaries

The ongoing development of That World includes a series of collaborative research and performance tests, notably with musicians Matthew Ford and Christobel Elliott. Invited as both critical users and creative co-researchers, their engagement was designed to challenge and extend the boundaries of what the system could achieve as both instrument and visual medium.

Ford and Elliott approached the installation as an open-ended ecosystem, its modular architecture allowing each musician to select elements for solo engagement or ensemble use. Both participants were encouraged to explore the reactive potential of the system, focusing on how bodily movement, instrumental gestures, and vocal nuance could be translated by the installation’s MIDI tracking and visual apparatus.

Matthew Ford: Guitar and Micro-Movement

Matthew Ford, a musical artist, sound engineer and founder of Tenth Court Records, focused on the system’s sensitivity to nuanced physical input. Using slow and minimal movement while recording improvisational guitar passages, Ford explored the degree to which That World’s sensors and sound architecture could detect and respond to micro-level physical shifts. Results showed that even the smallest gestures, changes in hand placement, posture, and attack, both seated or standing, could drive live adjustments in both the kinetic synthesizer’s progression and the visual mapping of audio-to-motion. This process enabled both fully live performance and the capturing of isolated elements for post-production editing, underlining the system’s adaptability and granular responsiveness.

Christobel Elliott: Vocal Accompaniment and Sonic Engagement

Christobel Elliott, a vocalist, multimedia artist and founder of RYMS, tested That World through improvised vocal accompaniment. As Elliott performed, the system reacted dynamically: the synthesizer’s MIDI trajectory and the evolving projections tracked both the pitch and movement of the voice and body, transforming the performance into a multisensory feedback loop. Notably, Elliott’s session demonstrated that vocal improvisation could not only command the engagement of the installation but also shape its ongoing context, creating a sustained dialog between performer, instrument, and visual system.

Key Findings

-

Boundary Testing: Both Ford’s guitar and Elliott’s voice revealed that That World could respond to wide gradations of performative intensity, from minute gestures to full-bodied movement, thereby confirming the system’s flexibility and modular control.

-

Live/Editable Duality: Each test facilitated both a live performance (in which engagement was visually and sonically immediate) and the creation of post-editable parts, enabling the work to function as both process and product.

-

Constant Engagement: The cyclic, MIDI-tracked synthesizer ensured performers remained engaged; its response was neither static nor overly predictable, requiring the musicians to continually adjust, experiment, and co-create.

-

Visual-Audio Integration: The reactive visuals successfully mapped the movement and sound of performers, further fusing music, motion, and image into a unified experience.

Implications

The success of Ford and Elliott’s sessions demonstrates that That World is a genuinely participatory and adaptive art-technology ecosystem, one that accepts not only different forms of input but also different approaches to mastery. The system’s cyclic engagement invites performers into a dialogue with the installation, generating complex and editable interactions that parallel the lived experience of neurodivergent cognition, continuous, flexible, and context-dependent.

-

Finn, S. (2023). “Nothing to Speak Of.” Think, Cambridge Core.

-

Finn, S. (2021). “The Metaphysics of Nothing.” Philosophy Bites.

-

Harman, G. (2018). Object-Oriented Ontology.

-

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter.

-

Bourriaud, N. (1998). Relational Aesthetics.

-

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells.

-

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway.

-

Le Guin, U. K. (1971). The Lathe of Heaven.

-

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus.

Copyright © 2025 Daniel Ford (Endless Prowl) All Rights Reserved

Endless Prowl respectfully acknowledges the true owners of the land on which this work was created, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. Endless Prowl pays respects to elders past, present and future, and acknowledges that sovereignty has never been ceded.